“In the past a lot of S&P 500 CEOs wished they had started thinking sooner than they did about their Internet strategy. I think five years from now there will be a number of S&P 500 CEOs that will wish they’d started thinking earlier about their AI strategy.” Andrew Ng

Introduction

Artificial intelligence changes our understanding of the world, of others and of ourselves. Already today, the catchword „AI“ can deeply unsettle people: „As an optimization machine, algorithmic automation mills its patterns in ever shorter intervals into the functional conditions of entire areas of life, work and society” (Martini 2019, V) and leaves behind diffuse fears and worries as well as pious wishes and hopes. Hardly any data-driven company can escape this confused state of mind. The economic success of an AI strategy also depends on the social acceptance of the new technologies. Confidence-building and transparency-increasing measures therefore play an increasingly important role in the success or failure of AI projects.

Based on the legal regulatory recommendation of Martini (2019), but also in contrast to a blind ideology of transparency, this contribution traces the potential of Corporate Responsibility (CR) and outlines how CR can be anchored within the framework of a sustainable AI strategy. The entrepreneurial scope does not only encompass promising opportunities and possibilities for counteracting excessive government regulation measures that could curb technical innovations. Rather, it also spans the trust horizon of digital society over basic social values. In this sense, companies are important players to count on if we want to shape digital society in a humane manner. Thinking ahead at this point leads us to the digital self-determination of people and to a practice-oriented interpretation of the concept of transparency using the example of a tiered information system or user cockpit. Like this, companies can offer their customers targeted solutions to contextually control what happens around their own data. To end our thoughts, a module for a trustworthy use of data will be integrated into the new concept of „Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR)“, which has already been discussed in various contexts.

Perception of Corporate Responsibility

According to the jurist Mario Martini (since July 2018 a member of the Data Ethics Commission of the German Federal Government), companies are committed to abide by the principles of transparency and data economy when processing personal data only under two premises: „if they are either forced to do so by regulation or if the customer’s wish gives them the choice of respecting their right to self-determination or of allowing the data stream to dry up“ (Martini 2019, VII).

Morally, the right to self-determination is deeply rooted in the idea of a free society. Critical voices however see the guarantee that people can set the standards by which they want to live, seriously threatened through the increasing „datafication of the world“ (cf. Filipović 2015, p. 6–15). Since most people in Europe know little about algorithms and a large part of the population is in a state of discomfort and disorientation (cf. Fischer und Petersen 2018; Grzymek und Puntschuh 2019), the call for further state regulation – especially in the context of artificial intelligence – is becoming increasingly clear (cf. Budras 2019).

Government and political action are based on the fundamental values of our society represented in the Constitution. Therefore, the current debate is no longer about the question of „whether“ but „how“ the population can be introduced to a self-determined handling of algorithmic and data-driven automation („artificial intelligence“). Before we examine the solution of a staged information system for user data, the so-called black box problem, which is often cited as reason for the lack of transparency of algorithmic systems, is first highlighted. According to Martini (2019), there are two different causes for the current lack of transparency: 1) Legal causes, insofar as algorithms are evaluated as official or business secrets, and 2) Technical causes, if the technical operation mode of „artificial intelligence“ appears to be impenetrable for the human mind.

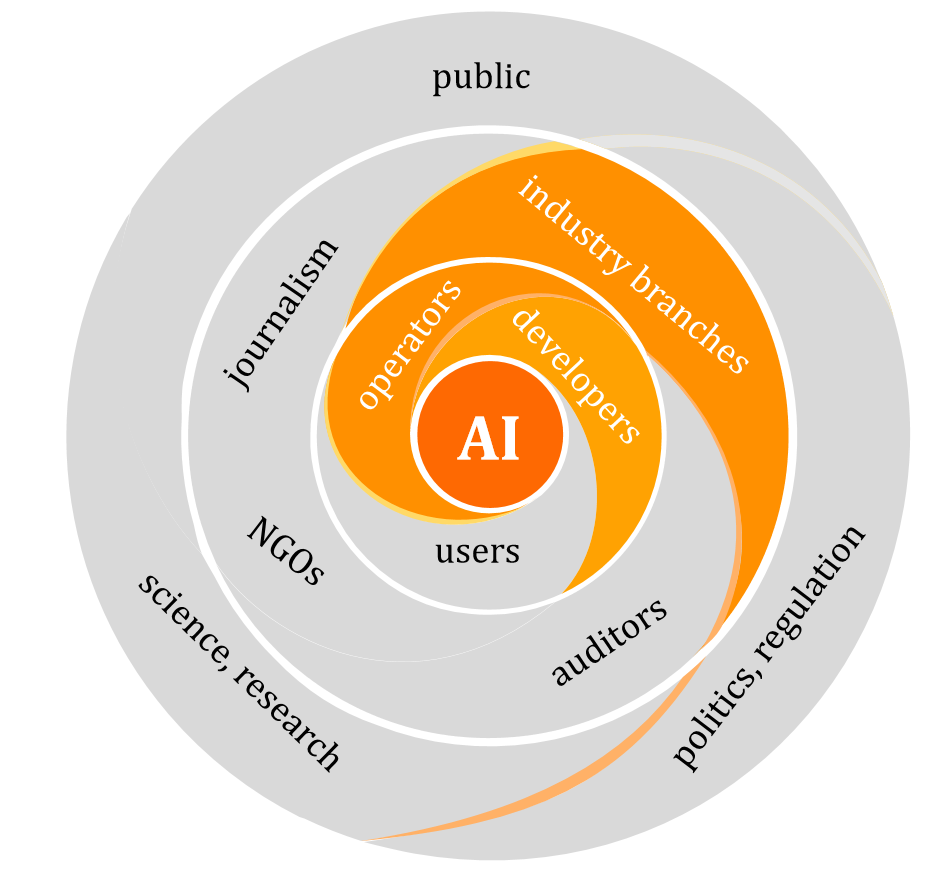

For a detailed explanation as to why „the previously applicable law, in particular data protection law, but also anti-discrimination and competition law […] does not yet specifically take into account the constitutional mandate“ (ibid. p. 109), we can refer to the monograph of Martini (2019). Building on these findings, the aim of this article is to show ways in which companies can take responsibility for shaping the scope currently available to them in order to develop potentially promising technologies within the framework of our fundamental social values. The two motives for action already cited above (regulatory compulsion and customer satisfaction) can be anchored in a third motive for action: corporate digital responsibility. The insight that data-driven companies have a special responsibility for AI from a practice-oriented perspective can be illustrated by the following graphic (based on Saurwein 2018):

Corporate responsibility concentrates on the innermost shell of the „onion of responsibility“, initially on the operators and developers of AI systems, but also on cooperation with industry associations on the second shell (both coloured orange). Since developers and operators – in contrast to the users – have privileged access to the behaviour and working methods of AI, the perception and recognition of one’s own responsibility is the most important basis for a sustainable solution to the current black box problem.

Criticism of the blind ideology of transparency

The concept of transparency is extremely complex in the context of digitisation. „No other buzzword today dominates public discourse as much as transparency“ (Han 2015). On the one hand, the term stands for the widespread fear of observation and the “glass human being” on the internet, for a danger to privacy and individual personality development (cf. Lück 2013). On the other hand, an ethical ideal is formed under the social demand for transparency, which is cited as an all-purpose weapon against opaque power structures, political and economic dependencies, conflicts of interest, corruption, data abuse and much more. The moral question that can be added to this discussion is: who or what should be transparent to whom?

Regarding the use of highly automated decisions, it is essentially a question of making the origination of such decisions visible and understandable to the persons affected by them. This is necessary because only then can those affected assess whether they should take the risks that may result from an AI-based evaluation, or not. The introduction of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has already strengthened individual rights. However, the transparency requirement from Art. 12 GDPR can only make a limited contribution, as Martini also states: „Often consumers do not accept well-intentioned consumer information under the time restrictions of everyday life or perceive it as an annoying dowry that merely follows a formalism and in the worst case raises more questions than answers“ (Martini 2019, p. 345).

Martini therefore recommends establishing the option in Art. 12 (7) GDPR for the use of standardised pictorial symbols (e.g. a red map marker pin for the use of anonymous geodata) which previously existed on a voluntary basis, as a „normative requirement specification“ (Martini 2019, p. 345). The combination of written information and pictorial symbols aims at „providing a meaningful overview of the intended data processing in an easily perceptible, understandable and clearly comprehensible form“ (Gola et al. 2017, p. 56). This is not only a matter of better orientation in the sense of data protection transparency, but above all also of enforcing the decision-making and intervention rights of the persons concerned, which are fundamental for guaranteeing informational selfdetermination (personal rights) (cf. ibid. p. 319). Against this background, Martini continues: „Users should not only act in an informed manner, but should also be able to exercise sovereignty over their data to the greatest extent possible in individual cases via a user cockpit, in particular be able to grant and withdraw rights of disposal and trace access to data“ (Martini 2019, p. 345).

In the implementation of the GDPR, the concept of transparency has so far mostly been reduced to the concept of informational self-determination. The only way for potential customers to exercise control is for them to consent to or object to the processing of their own data. This approach is based on a minimal concept of autonomy, since the declaration of consent required for data processing is usually a one-time informed consent – which many companies regard as fulfilled even if they refer to the improvement of their products and services as general purpose. The question of how much freedom of choice or action exists for the users within the technical system or which conditions must be fulfilled for interaction with complex algorithmic systems in order to speak of transparency or personal autonomy – even after the first declaration of consent – remains problematic. What makes an action an autonomous and self-determined action? This question is the key to the formulation of targeted transparency requirements, as the idea of digital selfdetermination (and of many other fundamental values, such as the moral status of a person, human dignity, etc.) can be traced to the concept of personal autonomy: „Whoever is autonomous controls his directly given motives or controls himself through self-chosen goals by accepting them, approving them, identifying himself with them, appreciating them or else rejecting them, not letting them become effective, disapproving of them and distancing himself from them“ (Betzler 2013, p. 12). The condition of authenticity adds that „what a person approves and by which he controls himself should be something that is truly ‚his own‘ and ‚really distinguishes‘ him“ (ibid., p. 13).

In the context of artificial intelligence, algorithmic profiling and the current black box debate, it makes sense to demand transparency requirements in addition to the control and authenticity conditions. This means that the filter criteria and selection mechanisms of AI should be transparent for the user, as otherwise it would not be possible to check whether the algorithmic decision criteria really correspond to one’s own motives and goals.

In order to sum up the criticism of a blind ideology of transparency, it is helpful to briefly reflect on the two extreme poles of the transparency requirement:

i) As outlined above, minimum transparency is achieved if the legal minimum of information requirements (accord. to the GDPR etc.) is met. ii) Maximum transparency would supposedly be achieved if all motives, dangers and risks of data use were fully captured and disclosed at all times; if all personal data could be viewed by the data users at all times; if all details of the functional logic, such as the weighting of filter criteria and selection mechanisms – especially in the context of machine learning and with regard to algorithmic decisions – were explained in detail, etc.

Neither the legal minimum nor supposedly complete transparency fulfils the requirements to ensure the digital self-determination rights of the persons concerned in dealing with AI. In practice, the minimal concept of transparency usually allows only informed selfdetermination, since (more or less detailed) information on the purpose of data processing relates only to the time of consent. This form of static consent is extremely inefficient both for the individual and for the data-driven industry. The latter already rightly points out that the proactive duty to provide information massively slows down the innovation potential of AI in Europe. On the other hand, the information for those concerned usually remains very vague and general – for example, when reference is made „to improve our services“ or „for the purpose of anonymizing data“. Data anonymisation is not only carried out to protect the privacy of the persons concerned (however usually only justified by this), but also because an evaluation of so-called anonymised affinity models no longer falls under the special protection for personal data in the GDPR. In most cases it is not mentioned that the collective character of algorithms can easily undermine this logic of individual rights (cf. Jaume-Palasí und Spielkamp 2017). Nor which personal disadvantages and long-term social risks are associated with the dissolution of individual interests and actions in the „numerical generality“ of affinity models (Heesen 2018) according to the watering can principle, etc. With a maximum concept of transparency, the question arises as to how a scientific treatise on such complex socio-technical details can concretely help the average citizen. Since too much information usually leads to a lack of transparency (cf. Ananny und Crawford 2016) the question of the right measure is more the focus of attention. From a scientific and legal perspective, it is of course important to penetrate all the interpretation methods of black box analyses mathematically and logically, to find new models and deeper insight. For the vast majority of users, a detailed explanation system that represents all factors for a particular prediction or behaviour would be counterproductive, because people prefer short and contextual explanations for an event in their everyday lives (cf. Miller 2017; Doshi-Velez und Kim 2017; Molnar 2019). In order to build lasting trust in AI applications, it is therefore primarily a matter of preparing the sometimes-agnostic interpretability of statistical models for specific target groups.

Transparency as part of a tiered information system

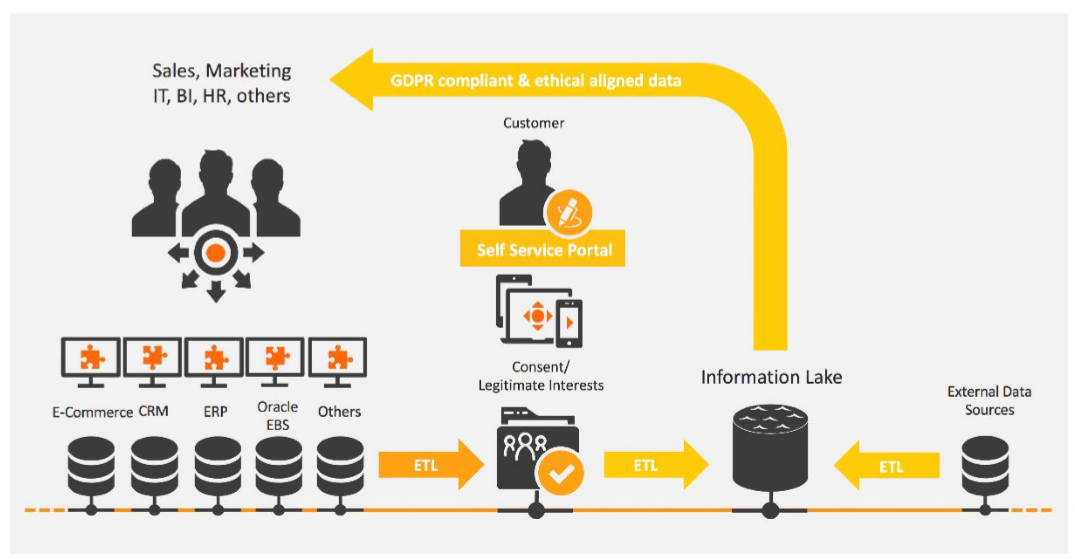

Digital self-determination is located at the abstraction level, where transparency and control can be established for the individual user (cf. Koska 2015). Since the same level of knowledge cannot be assumed for all users, a tiered information system is suitable for this issue. For a quick general introduction to the topic, standardized picture symbols (see above) can be used, which – preferably – are displayed context-sensitively during a particular user action. Because not all information is helpful in every situation. At this level, complexity reduction is required. Comprehensive information should therefore be better separated and ideally linked or made accessible to users via a more detailed self-service portal (see illustration).

On the one hand, the users can – analogous to the non-digital world (cf. Nissenbaum 2010) – better decide when they want to share specific data (segments) with whom and for what purpose. In certain situations, e.g. regarding specific health issues or for the preparation of a long-term loan, it can of course be very useful for potential patients or customers to receive tailor-made offers based on individual goals and personal interests and not on numerical generality. On the other hand, by introducing a tiered information system or user cockpit, companies are not only fulfilling their information and transparency obligations. By upgrading the „data lake“ to an „information lake“, cross-departmental authorisation concepts can be realised, internal data governance processes optimised, data quality improved and much more.

Implementing Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR)

Transparency can create trust. However, transparency mostly only exists as a futuristic vanishing point, see also Schneider (2013): “It becomes apparent that ‘transparency’ can only ever be promised. There is no transparency here and now.“ An increase always seems possible. To assume that transparency in terms of data protection, as it has already been compulsory introduced by the GDPR, is sufficient to guarantee digital self-determination, ignores the actual living conditions of the persons concerned, just the same as blind ideology of transparency. Companies that recognise this and are aware of their own responsibilities are currently in a particularly privileged position. Due to the changed communication and information possibilities (between companies, current customers and potential customers), businesses can use the (still) existing creativity scope to raise the concept of digital self-determination to a new level for their customers and to distinguish themselves from competitors. If they succeed in taking the customer with them on their journey toward digital responsibility, the customer will be able to build lasting trust in algorithmic decisions. The journey does not end with self-commitment codes, general statements of transparency and promotionally effective AI guidelines, it continues by letting the customer participate in holding the rudder and becoming an integral part of the AI responsibility strategy of companies (see Ackermann 2017).

In Germany, an intensive exchange between science, politics and companies has been taking place for several months now under the banner of „Corporate Digital Responsibility“ (cf. Altmeppen und Filipović 2019). This involves the voluntary integration of social and ecological concerns into the digitisation strategy of companies. Digitally responsible action therefore means not only complying with legal regulations, but also creating social, ecological and economic added value through ethical and sustainable corporate activities beyond mere legal conformity. This enables companies to enhance their reputation and at the same time create a solid basis of trust for digital innovations.

Quellen und Referenzen:

Ackermann, Gabriele (2017): CSR in der gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung. In: Alexandra Hildebrandt und Werner Landhäußer (Hg.): CSR und Digitalisierung. Der digitale Wandel als Chance und Herausforderung für Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 947-960.

Altmeppen, Klaus-Dieter; Filipović, Alexander (2019): Corporate Digital Responsibility. Zur Verantwortung von Medienunternehmen in digitalen Zeiten. In: Communicatio Socialis 52 (2).

Ananny, Mike; Crawford, Kate (2016): Seeing without knowing. Limitations of the transparency ideal and its application to algorithmic accountability. In: New Media & Society 33 (4), 146144481667664. DOI: 10.1177/1461444816676645.

Budras, Corinna (2019): Ein Gesetzbuch für Roboter. Hg. v. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Online available: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wissen/regulierung-der-ki-eingesetzbuch-fuer-roboter-16247534.html?GEPC=s5.

Doshi-Velez, Finale; Kim, Been (2017): Towards A Rigorous Science of Interpretable Machine Learning. Online available: http://arxiv.org/pdf/1702.08608v2.

Filipović, Alexander (2015): Die Datafizierung der Welt. Eine ethische Vermessung des digitalen Wandels 48 (1). Online available: http://ejournal.communicatiosocialis.de/index.php/cc/article/view/901/899.

Fischer, Sarah; Petersen, Thomas (2018): Was Deutschland über Algorithmen weiß und denkt. Hg. v. Bertelsmann Stiftung. Online available: https://algorithmenethik.de/wpcontent/uploads/sites/10/2018/05/Was-die-Deutschen-%C3%BCber-Algorithmendenken_ohneCover.pdf.

Gola, Peter; Eichler, Carolyn; Franck, Lorenz; Klug, Christoph; Lepperhoff, Niels (Hg.) (2017): Datenschutz-Grundverordnung. VO (EU) 2016/679 : Kommentar. München: C.H. Beck.

Grzymek, Viktoria; Puntschuh, Michael (2019): Was Europa über Algorithmen weiß und denkt. Hg. v. Bertelsmann Stiftung. Online available: https://www.bertelsmannstiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/WasEuropaUEberAlg orithmenWeissUndDenkt.pdf.

Han, Byung-Chul (2015): Transparenzgesellschaft. 1. Aufl. s.l.: Matthes Seitz Berlin Verlag. Online available: http://gbv.eblib.com/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=4346308.

Jaume-Palasí, Lorena; Spielkamp, Matthias (2017): Ethik und algorithmische Prozesse zur Entscheidungsfindung oder -vorbereitung. Arbeitspapier 4. Hg. v. Algorithm Watch. Online available: https://algorithmwatch.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/06/AlgorithmWatch_Arbeitspapier_4_Ethik_und_Algorithmen.p df.

Koska, Christopher (2015): Zur Idee einer digitalen Bildungsidentität. In: Harald Gapski (Hg.): Big Data und Medienbildung. Zwischen Kontrollverlust, Selbstverteidigung und Souveränität in der digitalen Welt. Düsseldorf, München: kopaed (Schriftenreihe zur digitalen Gesellschaft NRW, 3), p. 81–93. Online available: http://www.grimmeinstitut.de/schriftenreihe/downloads/srdg-nrw_band03_big-data-undmedienbildung.pdf.

Lück, Anne-Kathrin (2013): Der gläserne Mensch im Internet. Ethische Reflexionen zur Sichtbarkeit, Leiblichkeit und Personalität in der Online-Kommunikation. Zugl.: Zürich, Univ., Diss., 2012 u.d.T.: Lück, Anne-Kathrin: Zwischen Sichtbarkeit und Gläsernheit : ethische Überlegungen zur Kommunikation in sozialen Netzwerken und OnlineBewertungsportalen. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer (Forum Systematik, 45). Online available: http://d-nb.info/1034216120/04.

Martini, Mario (2019) (in print): Blackbox Algorithmus – Grundfragen einer Regulierung Künstlicher Intelligenz. Unter Mitarbeit von Michael Kolain und Jan Mysegades: Springer.

Miller, Tim (2017): Explanation in Artificial Intelligence: Insights from the Social Sciences. Online available: http://arxiv.org/pdf/1706.07269v3.

Molnar, Christoph (2019): Interpretable Machine Learning. A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable. Online available: https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-mlbook/.

Nissenbaum, Helen Fay (2010): Privacy in context. Technology, policy, and the integrity of social life. Stanford, California: Stanford Law Books an imprit of Standford University Press. Online available: http://site.ebrary.com/lib/academiccompletetitles/home.action.

Schneider, Manfred (2013): Transparenztraum. Literatur, Politik, Medien und das Unmögliche. 1. Aufl. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz. Online available: http://subhh.ciando.com/book/?bok_id=1016191.

Um einen Kommentar zu hinterlassen müssen sie Autor sein, oder mit Ihrem LinkedIn Account eingeloggt sein.